Average # of Babies Born Each Day in Us

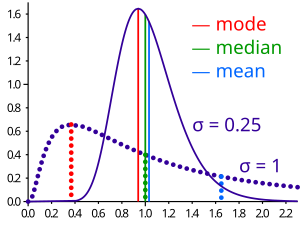

In simple language, an average is a single number taken every bit representative of a listing of numbers, usually the sum of the numbers divided by how many numbers are in the list (the arithmetic mean). For example, the average of the numbers ii, 3, iv, 7, and 9 (summing to 25) is 5. Depending on the context, an average might be another statistic such as the median, or fashion. For example, the average personal income is often given equally the median—the number below which are fifty% of personal incomes and above which are l% of personal incomes—considering the mean would exist misleadiningly high by including personal incomes from a few billionaires.

General properties [edit]

If all numbers in a listing are the same number, and so their average is also equal to this number. This belongings is shared past each of the many types of boilerplate.

Another universal property is monotonicity: if 2 lists of numbers A and B have the same length, and each entry of listing A is at least as large as the corresponding entry on listing B, so the boilerplate of list A is at least that of list B. Also, all averages satisfy linear homogeneity: if all numbers of a listing are multiplied by the same positive number, then its average changes past the same factor.

In some types of average, the items in the list are assigned different weights earlier the boilerplate is determined. These include the weighted arithmetic mean, the weighted geometric mean and the weighted median. Also, for some types of moving average, the weight of an detail depends on its position in the listing. Nearly types of average, however, satisfy permutation-insensitivity: all items count as in determining their average value and their positions in the list are irrelevant; the average of (1, 2, iii, four, half-dozen) is the same as that of (3, 2, half dozen, four, ane).

Pythagorean ways [edit]

The arithmetic mean, the geometric mean and the harmonic mean are known collectively equally the Pythagorean means.

Statistical location [edit]

The style, the median, and the mid-range are often used in addition to the mean as estimates of primal tendency in descriptive statistics. These can all be seen every bit minimizing variation past some measure; encounter Cardinal tendency § Solutions to variational bug.

| Type | Description | Example | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arithmetics mean | Sum of values of a data gear up divided by number of values: | (1+two+2+iii+4+7+9) / 7 | iv |

| Median | Middle value separating the greater and lesser halves of a data set | ane, 2, 2, 3, 4, 7, ix | 3 |

| Mode | Near frequent value in a data gear up | 1, 2, 2, 3, iv, vii, 9 | 2 |

| Mid-range | The arithmetic mean of the highest and lowest values of a set | (1+9) / two | 5 |

Mode [edit]

The about oftentimes occurring number in a list is chosen the mode. For instance, the way of the list (1, ii, two, 3, three, 3, 4) is 3. Information technology may happen that there are ii or more numbers which occur equally oft and more often than whatever other number. In this case at that place is no agreed definition of mode. Some authors say they are all modes and some say there is no mode.

Median [edit]

The median is the centre number of the grouping when they are ranked in order. (If at that place are an even number of numbers, the hateful of the eye two is taken.)

Thus to find the median, society the list according to its elements' magnitude and then repeatedly remove the pair consisting of the highest and lowest values until either one or two values are left. If exactly one value is left, it is the median; if two values, the median is the arithmetic hateful of these two. This method takes the listing 1, vii, iii, xiii and orders it to read 1, 3, 7, 13. And so the ane and xiii are removed to obtain the list three, 7. Since there are two elements in this remaining listing, the median is their arithmetic mean, (three + 7)/2 = 5.

Mid-range [edit]

The mid-range is the arithmetic mean of the highest and lowest values of a prepare.

Summary of types [edit]

| Name | Equation or clarification |

|---|---|

| Arithmetic mean | |

| Median | The middle value that separates the higher one-half from the lower half of the data set |

| Geometric median | A rotation invariant extension of the median for points in Rn |

| Manner | The nigh frequent value in the information set |

| Geometric mean | |

| Harmonic mean | |

| Quadratic mean (or RMS) | |

| Cubic mean | |

| Generalized mean | |

| Weighted hateful | |

| Truncated mean | The arithmetic mean of data values later on a certain number or proportion of the highest and lowest data values take been discarded |

| Interquartile mean | A special case of the truncated hateful, using the interquartile range. A special example of the inter-quantile truncated hateful, which operates on quantiles (often deciles or percentiles) that are equidistant but on contrary sides of the median. |

| Midrange | |

| Winsorized mean | Similar to the truncated mean, merely, rather than deleting the extreme values, they are set equal to the largest and smallest values that remain |

The table of mathematical symbols explains the symbols used below.

Miscellaneous types [edit]

Other more sophisticated averages are: trimean, trimedian, and normalized mean, with their generalizations.[1]

Ane tin can create i's ain boilerplate metric using the generalized f-mean:

where f is any invertible role. The harmonic hateful is an example of this using f(x) = one/x, and the geometric hateful is another, using f(x) = logx.

Still, this method for generating ways is non general plenty to capture all averages. A more general method[2] for defining an average takes any function one thousand(x 1,ten 2, ...,x n ) of a list of arguments that is continuous, strictly increasing in each argument, and symmetric (invariant under permutation of the arguments). The average y is and so the value that, when replacing each member of the list, results in the same function value: yard(y, y, ..., y) = g(10 1, x 2, ..., x northward ). This almost general definition yet captures the important property of all averages that the average of a list of identical elements is that element itself. The function one thousand(x 1, x 2, ..., x n ) = ten 1+ten 2+ ··· + ten north provides the arithmetic mean. The function one thousand(x 1, ten 2, ..., x north ) = x 1 10 two···x n (where the list elements are positive numbers) provides the geometric hateful. The part 1000(x 1, x ii, ..., x n ) = −(ten i −ane+x 2 −1+ ··· + ten n −ane) (where the listing elements are positive numbers) provides the harmonic mean.[2]

Average percent render and CAGR [edit]

A blazon of average used in finance is the boilerplate percent return. Information technology is an instance of a geometric hateful. When the returns are annual, it is called the Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR). For example, if we are considering a menstruum of 2 years, and the investment return in the commencement twelvemonth is −x% and the return in the 2d year is +60%, and so the average per centum render or CAGR, R, can be obtained by solving the equation: (one − 10%) × (ane + 60%) = (1 − 0.1) × (one + 0.6) = (1 + R) × (1 + R). The value of R that makes this equation true is 0.2, or twenty%. This means that the total render over the two-year period is the same as if at that place had been 20% growth each twelvemonth. The society of the years makes no difference – the average percentage returns of +60% and −10% is the same result as that for −10% and +sixty%.

This method can be generalized to examples in which the periods are not equal. For example, consider a period of a one-half of a year for which the return is −23% and a period of ii and a half years for which the return is +thirteen%. The average percentage return for the combined period is the single twelvemonth render, R, that is the solution of the following equation: (ane − 0.23)0.5 × (1 + 0.xiii)two.v = (1 + R)0.5+ii.5 , giving an boilerplate return R of 0.0600 or six.00%.

Moving average [edit]

Given a time series, such equally daily stock marketplace prices or yearly temperatures, people often want to create a smoother series.[3] This helps to bear witness underlying trends or peradventure periodic beliefs. An piece of cake manner to do this is the moving average: one chooses a number n and creates a new series by taking the arithmetic mean of the first n values, then moving forward one place past dropping the oldest value and introducing a new value at the other end of the list, and so on. This is the simplest form of moving average. More complicated forms involve using a weighted average. The weighting tin be used to enhance or suppress various periodic behavior and there is very extensive analysis of what weightings to utilize in the literature on filtering. In digital signal processing the term "moving average" is used fifty-fifty when the sum of the weights is non ane.0 (and then the output series is a scaled version of the averages).[4] The reason for this is that the analyst is normally interested merely in the trend or the periodic behavior.

History [edit]

Origin [edit]

The first recorded fourth dimension that the arithmetics mean was extended from 2 to n cases for the use of estimation was in the sixteenth century. From the belatedly sixteenth century onwards, information technology gradually became a mutual method to utilise for reducing errors of measurement in various areas.[v] [6] At the fourth dimension, astronomers wanted to know a existent value from noisy measurement, such every bit the position of a planet or the diameter of the moon. Using the mean of several measured values, scientists assumed that the errors add upwardly to a relatively pocket-sized number when compared to the total of all measured values. The method of taking the mean for reducing ascertainment errors was indeed mainly adult in astronomy.[5] [7] A possible precursor to the arithmetics mean is the mid-range (the mean of the ii extreme values), used for case in Arabian astronomy of the ninth to eleventh centuries, simply too in metallurgy and navigation.[6]

Yet, at that place are various older vague references to the utilise of the arithmetics mean (which are not as articulate, merely might reasonably have to do with our modern definition of the mean). In a text from the 4th century, information technology was written that (text in square brackets is a possible missing text that might clarify the meaning):[viii]

- In the first identify, nosotros must set out in a row the sequence of numbers from the monad upwards to nine: i, 2, 3, 4, 5, half dozen, 7, eight, 9. And then nosotros must add together up the amount of all of them together, and since the row contains nine terms, we must look for the ninth office of the total to see if it is already naturally present among the numbers in the row; and we will notice that the property of being [one] ninth [of the sum] but belongs to the [arithmetics] mean itself...

Fifty-fifty older potential references exist. In that location are records that from almost 700 BC, merchants and shippers agreed that impairment to the cargo and ship (their "contribution" in case of damage by the body of water) should be shared equally amongst themselves.[7] This might have been calculated using the boilerplate, although there seem to exist no straight record of the calculation.

Etymology [edit]

The root is institute in Arabic as عوار ʿawār, a defect, or anything defective or damaged, including partially spoiled merchandise; and عواري ʿawārī (also عوارة ʿawāra) = "of or relating to ʿawār, a country of fractional damage".[9] Inside the Western languages the word's history begins in medieval sea-commerce on the Mediterranean. 12th and 13th century Genoa Latin avaria meant "impairment, loss and not-normal expenses arising in connection with a merchant body of water voyage"; and the same meaning for avaria is in Marseille in 1210, Barcelona in 1258 and Florence in the late 13th.[10] 15th-century French avarie had the aforementioned meaning, and it begot English "averay" (1491) and English "average" (1502) with the same meaning. Today, Italian avaria, Catalan avaria and French avarie notwithstanding take the chief meaning of "damage". The huge transformation of the significant in English began with the practice in later medieval and early modernistic Western merchant-marine law contracts under which if the ship met a bad storm and some of the goods had to exist thrown overboard to make the transport lighter and safer, then all merchants whose goods were on the ship were to suffer proportionately (and non whoever'due south goods were thrown overboard); and more mostly there was to exist proportionate distribution of any avaria. From there the word was adopted by British insurers, creditors, and merchants for talking nigh their losses as being spread across their whole portfolio of assets and having a mean proportion. Today's meaning developed out of that, and started in the mid-18th century, and started in English.[x] [1].

Marine damage is either particular average, which is borne merely by the owner of the damaged holding, or general average, where the possessor can merits a proportional contribution from all the parties to the marine venture. The blazon of calculations used in adjusting full general boilerplate gave ascension to the use of "boilerplate" to mean "arithmetics mean".

A second English usage, documented as early on equally 1674 and sometimes spelled "averish", is every bit the residue and second growth of field crops, which were considered suited to consumption by draught animals ("avers").[eleven]

At that place is before (from at least the 11th century), unrelated utilise of the word. It appears to be an old legal term for a tenant'south day labour obligation to a sheriff, probably anglicised from "avera" found in the English language Domesday Book (1085).

The Oxford English Dictionary, however, says that derivations from German hafen oasis, and Standard arabic ʿawâr loss, harm, have been "quite disposed of" and the word has a Romance origin.[12]

Averages as a rhetorical tool [edit]

Due to the aforementioned colloquial nature of the term "boilerplate", the term tin be used to obfuscate the true meaning of data and suggest varying answers to questions based on the averaging method (nearly frequently arithmetic mean, median, or mode) used. In his commodity "Framed for Lying: Statistics every bit In/Artistic Proof", University of Pittsburgh faculty member Daniel Libertz comments that statistical information is frequently dismissed from rhetorical arguments for this reason.[xiii] However, due to their persuasive power, averages and other statistical values should not be discarded completely, but instead used and interpreted with caution. Libertz invites united states of america to engage critically non simply with statistical information such as averages, but also with the language used to describe the data and its uses, saying: "If statistics rely on interpretation, rhetors should invite their audience to interpret rather than insist on an estimation."[13] In many cases, data and specific calculations are provided to aid facilitate this audience-based interpretation.

See too [edit]

- Average absolute deviation

- Law of averages

- Expected value

- Key limit theorem

- Population hateful

- Sample hateful

References [edit]

- ^ Merigo, Jose K.; Cananovas, Montserrat (2009). "The Generalized Hybrid Averaging Operator and its Awarding in Decision Making". Periodical of Quantitative Methods for Economics and Business organisation Administration. 9: 69–84. ISSN 1886-516X. [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ a b Bibby, John (1974). "Axiomatisations of the average and a farther generalisation of monotonic sequences". Glasgow Mathematical Journal. 15: 63–65. doi:x.1017/s0017089500002135.

- ^ Box, George E.P.; Jenkins, Gwilym One thousand. (1976). Time Series Assay: Forecasting and Control (revised ed.). Holden-Day. ISBN0816211043.

- ^ Haykin, Simon (1986). Adaptive Filter Theory. Prentice-Hall. ISBN0130040525.

- ^ a b Plackett, R. L. (1958). "Studies in the History of Probability and Statistics: Vii. The Principle of the Arithmetic Mean". Biometrika. 45 (1/2): 130–135. doi:10.2307/2333051. JSTOR 2333051.

- ^ a b Eisenhart, Churchill. "The development of the concept of the best mean of a set of measurements from artifact to the present mean solar day." Unpublished presidential address, American Statistical Clan, 131st Annual Coming together, Fort Collins, Colorado. 1971.

- ^ a b Bakker, Arthur. "The early history of average values and implications for education." Journal of Statistics Instruction eleven.1 (2003): 17-26.

- ^ "Waterfield, Robin. "The theology of arithmetics." On the Mystical, mathematical and Cosmological Symbolism of the First Ten Number (1988). folio 70" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2018-11-27 .

- ^ Medieval Arabic had عور ʿawr meaning "blind in one eye" and عوار ʿawār meant "whatever defect, or anything defective or damaged". Some medieval Arabic dictionaries are at Baheth.info Archived 2013-ten-29 at the Wayback Machine, and some translation to English language of what's in the medieval Standard arabic dictionaries is in Lane's Arabic-English language Lexicon, pages 2193 and 2195. The medieval dictionaries do not list the give-and-take-form عوارية ʿawārīa. ʿAwārīa can be naturally formed in Standard arabic grammar to refer to things that have ʿawār, only in practice in medieval Standard arabic texts ʿawārīa is a rarity or non-real, while the forms عواري ʿawārī and عوارة ʿawāra are oftentimes used when referring to things that have ʿawār or harm – this can be seen in the searchable collection of medieval texts at AlWaraq.net (volume links are clickable on righthand side).

- ^ a b The Arabic origin of avaria was first reported by Reinhart Dozy in the 19th century. Dozy'south original summary is in his 1869 book Glossaire. Summary data near the give-and-take's early records in Italian-Latin, Italian, Catalan, and French is at avarie @ CNRTL.fr Archived 2019-01-06 at the Wayback Machine. The seaport of Genoa is the location of the earliest-known record in European languages, year 1157. A fix of medieval Latin records of avaria at Genoa is in the downloadable lexicon Vocabolario Ligure, by Sergio Aprosio, twelvemonth 2001, avaria in Volume 1 pages 115-116. Many more records in medieval Latin at Genoa are at StoriaPatriaGenova.it, usually in the plurals avariis and avarias. At the port of Marseille in the 1st half of the 13th century notarized commercial contracts take dozens of instances of Latin avariis (ablative plural of avaria), equally published in Blancard yr 1884. Some information most the English discussion over the centuries is at NED (year 1888). See as well the definition of English "boilerplate" in English dictionaries published in the early 18th century, i.e., in the fourth dimension flow simply before the big transformation of the meaning: Kersey-Phillips' dictionary (1706), Blount'south lexicon (1707 edition), Hatton's dictionary (1712), Bailey'due south dictionary (1726), Martin's dictionary (1749). Some complexities surrounding the English discussion'due south history are discussed in Hensleigh Wedgwood yr 1882 page 11 and Walter Skeat year 1888 page 781. Today there is consensus that: (#i) today's English "average" descends from medieval Italian avaria, Catalan avaria, and (#2) among the Latins the word avaria started in the 12th century and it started every bit a term of Mediterranean sea-commerce, and (#iii) at that place is no root for avaria to be constitute in Latin, and (#4) a substantial number of Arabic words entered Italian, Catalan and Provençal in the 12th and 13th centuries starting equally terms of Mediterranean sea-commerce, and (#5) the Arabic ʿawār | ʿawārī is phonetically a skillful friction match for avaria, as conversion of westward to five was regular in Latin and Italian, and -ia is a suffix in Italian, and the Western word's earliest records are in Italian-speaking locales (writing in Latin). And most commentators agree that (#6) the Arabic ʿawār | ʿawārī = "damage | relating to damage" is semantically a good match for avaria = "impairment or damage expenses". A minority of commentators have been dubious virtually this on the grounds that the early records of Italian-Latin avaria have, in some cases, a meaning of "an expense" in a more general sense – meet TLIO (in Italian). The majority view is that the meaning of "an expense" was an expansion from "damage and impairment expense", and the chronological guild of the meanings in the records supports this view, and the broad significant "an expense" was never the nearly commonly used meaning. On the basis of the above points, the inferential footstep is made that the Latinate word came or probably came from the Arabic word.

- ^ Ray, John (1674). A Drove of English Words Non More often than not Used. London: H. Bruges. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "boilerplate, n.2". OED Online. September 2019. Oxford University Press. https://world wide web.oed.com/view/Entry/13681 (accessed September 05, 2019).

- ^ a b Libertz, Daniel (2018-12-31). "Framed for Lying: Statistics as In/Creative Proof". Res Rhetorica. 5 (four). doi:10.29107/rr2018.4.1. ISSN 2392-3113.

External links [edit]

| | Look up average in Wiktionary, the free lexicon. |

- Median as a weighted arithmetic mean of all Sample Observations

- Calculations and comparison betwixt arithmetic and geometric mean of two values

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Average

![{\displaystyle {\sqrt[{n}]{\prod _{i=1}^{n}x_{i}}}={\sqrt[{n}]{x_{1}\cdot x_{2}\dotsb x_{n}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a3740b9924a63fcde06a3fd26d9691c082910d78)

![{\sqrt[ {3}]{{\frac {1}{n}}\sum _{{i=1}}^{{n}}x_{i}^{3}}}={\sqrt[ {3}]{{\frac {1}{n}}\left(x_{1}^{3}+x_{2}^{3}+\cdots +x_{n}^{3}\right)}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/87ea526bc6b48f6abb52bc522d57c9fedacbaf90)

![\sqrt[p]{\frac{1}{n} \cdot \sum_{i=1}^n x_{i}^p}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b914d893b094e9e15a5681ef60069e9e5fac54ab)

![y = f^{-1}\left(\frac{1}{n}\left[f(x_1) + f(x_2) + \cdots + f(x_n)\right]\right)](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5fea48be50f3fe5836ae433848e3e4ca0c9827a5)

0 Response to "Average # of Babies Born Each Day in Us"

Post a Comment